Collectively mapping London's vacant land

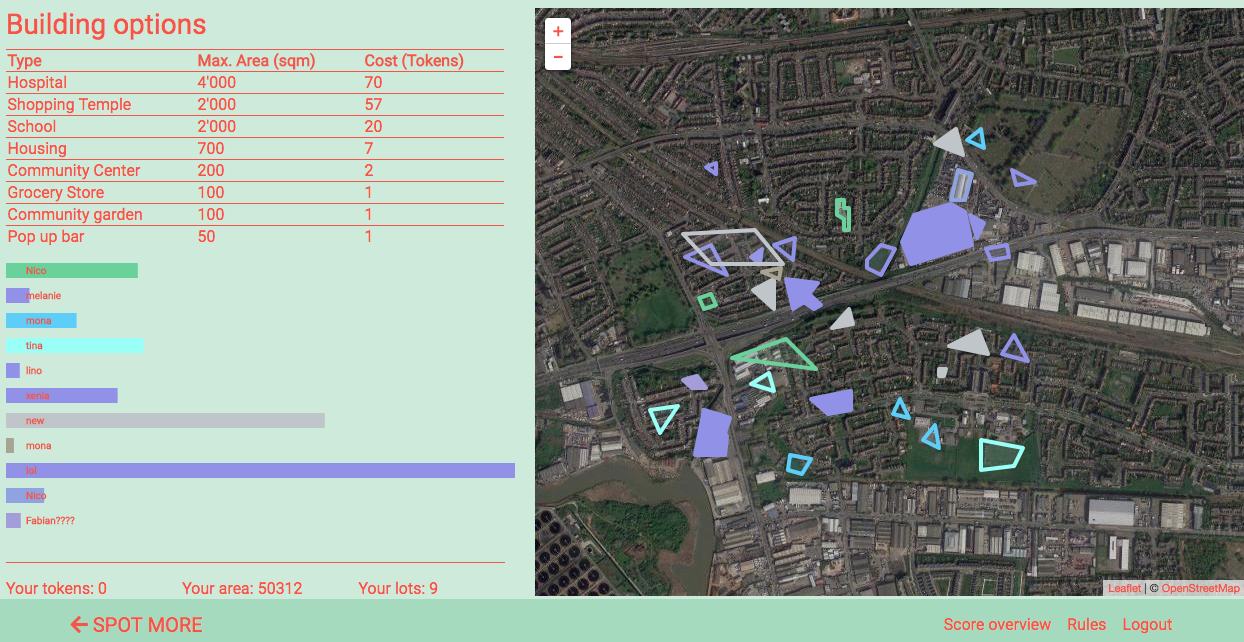

I am currently working on a web tool that aims to create a database of all vacant land in London through crowdsourcing for my Master’s thesis. Want to know more? Read below:

Why do we need a reliable database for vacant land?

According to think tank New Economic Foundation (NEF), groups looking to build community-led, affordable housing development in their area face one great obstacle: acquiring land (Martin, 2018). Many reasons prevent community groups from entering this game. Some of them relate to the lack of transparency when it comes to available ressources:

1) Inaccessibility of data: Land ownership data is restricted to public. Access to the LM Land Registry is not free of charge and can only be obtained for individual properties (Shrubsole, 2016).

2) Reliability of data: The redevelopment of brownfield sites and empty property is greatly constrained by a paucity of data (Myers and Wyatt, 2004). Research by the author has shown that although databases exist for both commercial and governmental property ownership and vacant land, both databases are erroneous, outdated and incomplete. In addition, about 18% of land in England and Wales is unregistered, and not even the government knows who owns it (Hookway, 2018).

Scope of thesis

Two pieces of information are essential for community groups interested in building: knowing the location of vacant land and knowing by whom it is owned. This thesis aims to explore gamified crowd sourced data collection methods to acquire data about land ownership and land vacancy. The methods will be tested in a proof-of-concept prototype. Previous studies highlight the following advantages of crowd sourcing:

1) Crowd sourced data collection: Collecting data through administrational bodies takes a long time whereas a crowd can rapidly generate data about circumstances affecting the crowd itself at little or no cost (Barbier et al., 2012). Based on the assumption that data about ownership and vacancy is outdated quickly, crowdsourcing methods have great potential.

2) Gamification in spatial processes: Krek (2005) observed that many citizens are “rationally ignorant”. According to the rational ignorance condition, citizens tend to ignore urban planning processes because participation would require a high investment of time and effort to ascertain the current planning situation. Poplin (2012), tries to overcome this condition by creating online serious games to bring playfulness and pleasure to the serious processes of urban planning decisions.

Case study background

Vacant land in London

In the year 2000, the government released a White Paper where councils were encouraged to use previously developed land and buildings are regenerated to maximize the use of existing resources (Davies et al., 2001). Using existing resources is important due to planning policies that restrict development on remaining greenfields and limitations relating to land ownership. However, the redevelopment of previously developed land, also referred to as brownfields, and empty property is greatly constrained by a lack of data (Myers and Wyatt, 2004). The following paragraphs describe the information that is publicly available and its deficits.

1) National Land Use Database of Previously Developed Land (2017)

The government has undertaken some efforts to provide a database of vacant land across England. The database NLUD-PDL, released by Homes and Communities Agency (HCA) in 2017 and part of the general National Land Use Database, classifies land into vacant buildings and previously developed land. It contains around 8000 entries including area size and point coordinates. As caveats, the authorities state that the dataset was never validated. In addition, out of the 326 local planning authorities in England, excluding National Parks, only 149 (45%) provided information.

2) London Brownfield Sites Database (2009)

The London Development Agency (LDA) and the Homes and Communities Agency (HCA) released a geospatial database of London’s brownfield land over 0.25ha. However, on the website it is stated that the brownfield sites dataset was integrated in the NLUD-PDL. Hence, will only be accessible as point data. Old versions including polygons can still be accessed from the London Data Store.

Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI)

A variety of terminologies describe information systems and processes that depend on participation, aided by digital means of the Web 2.0. Only some of them are described here in detail.

1) Crowdsourcing and citizen science

Crowdsourcing is perceived as a tool to gather ideas, innovations, or information for certain purposes from a large number of participants (Leiponen and Aitamurto, 2011). The value in harvesting the knowledge of individuals is based on the observation that, although a large number of individual estimates may be incorrect, their average can be a match for expert judgment. A random sample of the opinions of a large number of users might lead to data and information that is surprisingly accurate and that, in some cases, cannot be recorded in any other way (Surowiecki, 2004). Citizen science (Bonney et al. 2009) describes the broader involvement of citizens in a range of scientific activities from data collection to data analysis and research design (Hudson-Smith et al., 2009).

2) Spatial crowdsourcing: Participatory GIS (PGIS), Public Participation GIS (PPGIS), and Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI)

Concepts of citizen science can also be applied to geography. Many terms refer to this citizen involvement in geospatial sciences: These include ‘volunteered geographic information (VGI) (Goodchild, 2007), Participatory geographic information systems (PGIS), and Public participation GIS (PPGIS) (Dunn, 2007), to name a few. Regardless of the specific terminology, all of these activities share in common the distributed completion of small, clearly defined tasks (Hudson-Smith et al., 2009). VGI can enhance digital earth products, for instance by refining maps with tasks that machine learning algorithms struggle to perform (Salk et al., 2016). Prominent VGI activities focus on the creation of more elaborate representations of the Earth’s surface. OpenStreetMap is an international effort to create a free source of map data through volunteer effort (Goodchild, 2007). Missing Maps is a humanitarian project that preemptively maps parts of the world that are vulnerable to natural disasters, conflicts, and disease epidemics. Colouring London sets out to collect and share numerical and categorical data relating to the age and land use of buildings (Hudson, 2018). The Geo-Wiki project identifies locations where global land cover datasets disagree on a given land cover classification. It provides participants with aerial imagery, and asks them to make a classification choice for that location of disagreement (Sparks et al., 2015).

3) What about validating the output of VGI?

While VGI has proliferated in recent years, assessing the quality of volunteer-contributed data has proven challenging. There are many approaches to quality control for volunteer-contributed data (Salk et al., 2016). Allahbakhsh (2013), differentiates between the following eight approaches: Expert review, Output agreement, Input agreement, Ground truth, Majority consensus, Contributor evaluation, real-time support and Workflow management.

EDIT: Just recently, the online news platform Citylab published an interesting article on the topic of land vacancy, land banking and property guardianship. Read here: https://www.citylab.com/solutions/2018/10/londons-empty-spaces/572011/

subscribe to the tag via RSS